Accounting and Reporting Challenges in Brand Valuation

Accounting and Reporting Challenges in Brand Valuation

Accounting for brand value has long posed one of the most intellectually demanding challenges within the field of corporate reporting, primarily because it attempts to reconcile two fundamentally incompatible domains: the fluid, perception-driven nature of brands and the disciplined, rules-based nature of financial reporting. A brand exists not in physical form but within the collective consciousness of consumers, stakeholders, and markets. It is shaped by emotions, cultural associations, symbolic meanings, shared experiences, and accumulated trust. This psychological and social capital has undeniable economic impact—brands influence willingness to pay, customer loyalty, competitive insulation, international expansion potential, and long-term revenue stability. Yet, because brands are intangible concepts that cannot be touched, weighed, or easily verified, they conflict with the core financial reporting principles of reliability, objectivity, and verifiability.

This conflict becomes increasingly salient in the modern economy, where intangible assets dominate corporate value. In many sectors—technology, luxury, entertainment, financial services, consumer goods—the brand represents one of the most powerful economic drivers. Global valuation studies consistently show that a significant proportion of the market capitalization of leading corporations is derived from intangible factors such as brand equity, consumer loyalty, ecosystem access, and digital engagement. However, IFRS accounting rules continue to prioritize verifiability over economic relevance, resulting in a paradox in which the most valuable assets remain unrecognized on the balance sheet.

The disconnect between economic reality and accounting treatment creates a structural challenge for financial institutions, investors, regulators, and analysts who rely on financial statements to assess performance, risk exposure, and enterprise value. The invisibility of internally generated brands under IFRS leads to distortions in book value, asset structure, leverage ratios, return on asset calculations, and equity assessments. This invisibility is at the heart of brand reporting challenges IFRS, where the strict rules governing intangible asset recognition produce reports that cannot fully reflect modern business dynamics.

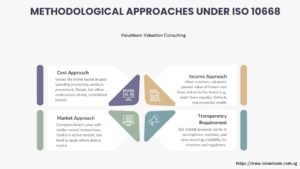

The complexity deepens when organizations attempt to assign value to brands through valuation techniques. Brand valuation methodologies—such as relief-from-royalty, multi-period excess earnings, or price premium analyses—require forward-looking assumptions about market behavior, consumer preferences, competitive movements, regulatory developments, technological shifts, and macroeconomic fluctuations. Each assumption introduces judgment, subjectivity, and uncertainty. These subjective components make it difficult to achieve absolute consistency in valuation across industries, jurisdictions, or timeframes, challenging auditors and preparers to justify assumptions under scrutiny.

Beyond the theoretical and procedural limitations, the challenges extend into practical corporate reporting environments. Management teams must balance strategic optimism with accounting conservatism. Auditors must assess whether valuation assumptions are reasonable and internally consistent. Regulators must ensure compliance without stifling meaningful disclosure. Investors must interpret imperfect information about brand value while making long-term decisions. These complexities underscore why brand valuation for financial reporting Singapore remains an area of profound difficulty and why academic researchers regard it as one of the most conceptually elusive aspects of modern financial reporting.

As intangibles become increasingly central to corporate performance, investors and stakeholders demand deeper insight into the factors driving brand strength. Markets now evaluate companies not only through financial ratios but through narrative indicators such as brand reputation, trustworthiness, innovation culture, sustainability alignment, customer engagement, digital presence, and social impact. Stakeholders seek clarity about how a company’s brand fits into its long-term growth strategy, industry positioning, competitive differentiation, and resilience against external risks.

However, IFRS frameworks heavily restrict the recognition of these intangible drivers. Internally generated brands cannot be capitalized, meaning investments in advertising, public relations, sustainability campaigns, digital branding, and customer experience enhancements—often costing hundreds of millions—are expensed immediately. This means financial statements show reduced profit in the short term but no intangible asset buildup, even though these expenditures create long-term economic value.

This clash between economic substance and accounting form intensifies the need for transparent narrative reporting. Companies must use management commentary, investor briefings, integrated reports, and sustainability disclosures to communicate aspects of brand performance not recognized in financial statements. Transparent narrative becomes a complementary reporting mechanism that bridges the gap between IFRS limitations and stakeholder expectations.

The demand for transparency is even more acute in Singapore, where governance standards are exceptionally high and the investor community is sophisticated. Singapore’s capital markets emphasize clarity, accountability, and discipline, requiring companies to articulate intangible value drivers despite reporting constraints. This leads to unique brand accounting issues Singapore, where companies must satisfy strict compliance standards while providing competitive-intelligence-sensitive insight into their brand strategy, customer base strength, and reputation resilience.

The tension between transparency and compliance creates a delicate balancing act. Companies must disclose enough information to satisfy regulatory and investor expectations while avoiding disclosures that may undermine competitive advantage or reveal proprietary strategies. This complexity defines the modern landscape of brand reporting in Singapore and globally, requiring a nuanced understanding of both valuation theory and regulatory practice.

Recognition Challenges Under IFRS

IFRS Restrictions on Internally Generated Brand Value

IAS 38 Intangible Assets establishes stringent criteria for the recognition of intangible assets, including brands. The standard differentiates between intangible assets acquired externally—such as through acquisition—and those developed internally. Internally generated brands do not meet the recognition criteria because their cost cannot be reliably measured and the future economic benefits cannot be definitively demonstrated in a way consistent with accounting verification requirements.

This prohibition on capitalization produces one of the most profound conceptual distortions in modern accounting. Consider a global luxury brand such as a high-end fashion house, a multinational consumer goods company, or a digital lifestyle brand. These organizations may spend decades cultivating brand recognition, investing in design innovation, marketing campaigns, influencer partnerships, cultural relevance, and experiential branding. These investments build extraordinary brand equity, resulting in premium pricing power, loyal customer bases, and global resonance. Yet under IFRS, none of this brand value appears on the balance sheet.

This creates an asymmetry between companies that grow organically and those that grow through acquisition. When a company acquires another company with a strong brand, IFRS requires recognition of brand value at fair value under IFRS 3 Business Combinations. This allows the acquirer to capitalize the acquired brand as an intangible asset. In contrast, a company that builds a similarly strong brand internally cannot capitalize it. This inconsistency impairs comparability and creates structural distortions in financial reporting, affecting investor interpretation and strategic decision-making.

This inconsistency also affects performance analysis. Key financial ratios such as return on assets (ROA), asset turnover, and leverage ratios become distorted. A company with a strong brand but an asset-light balance sheet may appear more efficient than a comparable company that grew through acquisition and therefore carries recognized intangible assets. Analysts must adjust for these differences to achieve accurate comparisons. The limitations of IAS 38 therefore create both conceptual and practical challenges, intensifying the need for supplementary narrative explanations to bridge the informational gap.

Valuation Issues in M&A Transactions

When a brand is acquired through a business combination, IFRS requires it to be recognized at its fair value on the acquisition date. This recognition triggers a necessity for thorough and defensible brand valuation. Valuation professionals must determine the economic benefits attributable specifically to the brand and assess how these benefits contribute to the total purchase consideration.

The valuation process is inherently complex. The relief-from-royalty method, one of the most widely used valuation techniques, estimates the hypothetical royalty payments that would be required if the company licensed the brand instead of owning it. This requires careful consideration of appropriate royalty rates, which vary by industry, geography, and market conditions. The determination of royalty rates introduces subjectivity, as it must reflect market comparator data, profit margins, competitive positioning, and industry norms.

In addition to royalty assumptions, valuation requires selecting appropriate discount rates that reflect the brand’s risk profile, market conditions, and competitive dynamics. Discount rates significantly influence valuation outcomes; small adjustments may lead to materially different fair value estimates. Further complexities arise in estimating revenue growth rates, forecasting brand influence on expansion potential, and assessing brand longevity. Companies must provide defendable, well-documented assumptions to satisfy auditors, regulators, and stakeholders.

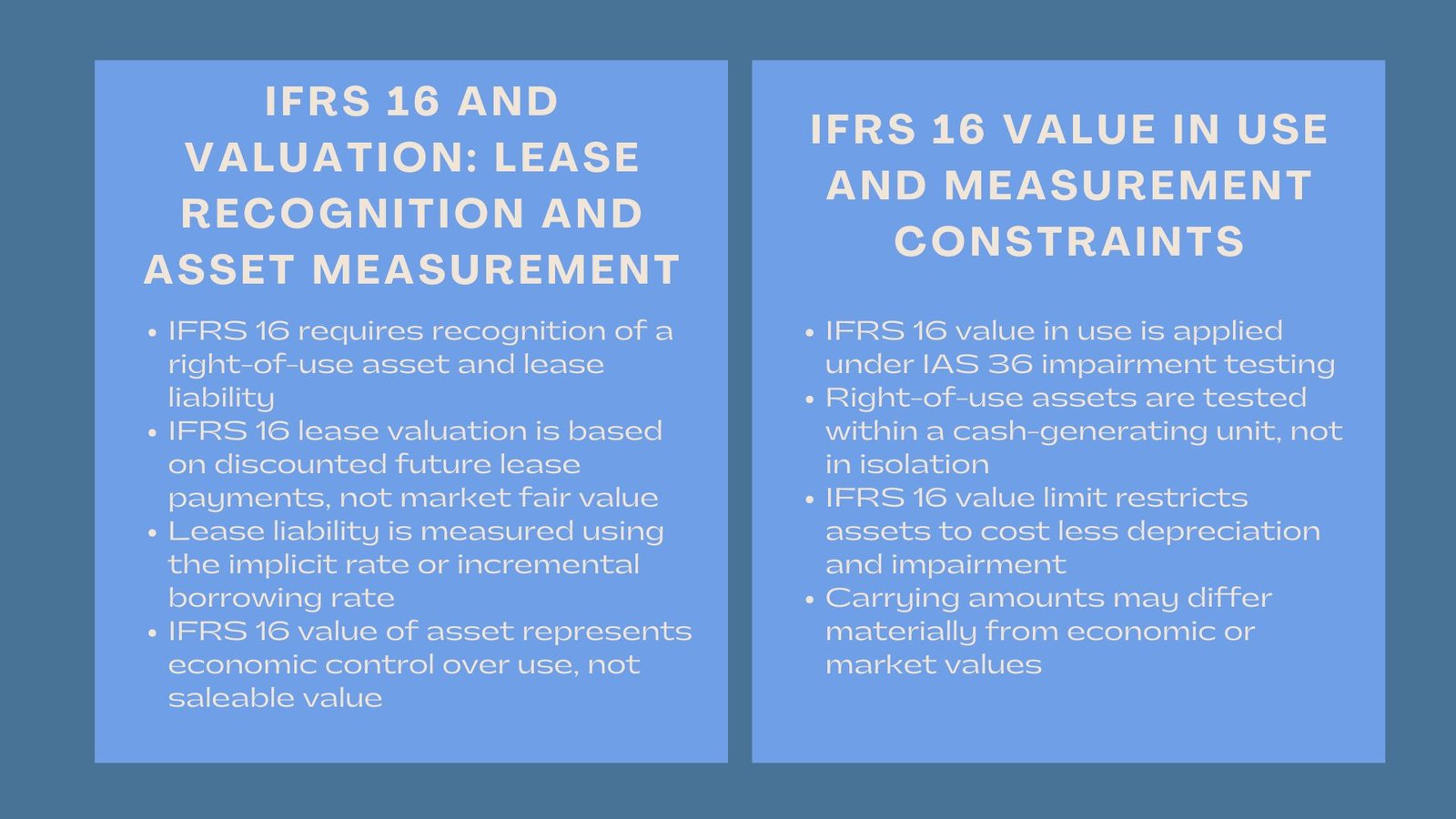

Following acquisition, brands must undergo impairment testing under IAS 36 if classified as indefinite-lived assets. Impairment testing requires ongoing estimation of recoverable amounts based on fair value less costs of disposal or value in use. Brands may require annual testing regardless of whether external indicators of impairment exist. Companies must anticipate changing market dynamics, competitive challenges, reputational risks, and shifts in customer preferences. Brands exposed to reputational scandals or market disruption may experience rapid declines in value, triggering impairment. The complexity of impairment testing underlines the extensive judgment required in brand reporting.

Reporting Challenges in Singapore

Complexity of Brand Accounting in a Singapore Context

Singapore occupies a unique position as a global business hub, regional headquarters center, and innovation-driven economy. Companies operating in Singapore often serve diverse Southeast Asian markets with heterogeneous consumer behaviors, cultural norms, digital maturity levels, price sensitivities, and brand associations. These differences create complexities when applying valuation methodologies that assume homogeneity in market perception.

A brand may enjoy exceptional strength in Singapore’s premium market but hold significantly weaker recognition in neighboring countries such as Vietnam, the Philippines, or Myanmar. The valuation must reflect these variations, requiring market-specific analyses that account for cultural differences, economic maturity, and competitive structures. These regional variations complicate brand valuation, particularly when determining market participant assumptions required under fair value measurement principles in IFRS 13.

Singapore’s economic structure also accentuates the importance of intangible assets. With limited natural resources, Singapore’s economy emphasizes intellectual capital, innovation, financial services, technology, and consumer brands. Companies often invest heavily in brand-building activities, from digital marketing to customer experience innovation and sustainability-driven branding. Yet these internally generated assets remain unrecognized under IFRS. This creates a growing divergence between corporate strategy and accounting representation, forming a core component of brand accounting issues Singapore.

These issues are not merely theoretical. They affect lending decisions, credit assessments, investor perception, and valuation multiples. Companies that emphasize intangible value creation may struggle to secure financing based solely on reported assets. Investors must conduct extensive external analysis to understand brand-driven performance, as financial statements do not fully reflect this value. This creates a reliance on supplementary reporting that extends beyond IFRS requirements.

Regulatory Scrutiny and Investor Expectations in Singapore

Singapore’s regulatory environment is characterized by rigor, transparency, and high-quality governance standards. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) and Singapore Exchange (SGX) promote strong compliance practices, accountability, and detailed disclosures. As a result, companies operating in Singapore face heightened scrutiny of brand-related financial reporting.

Investors expect meaningful insights into brand strategy, risk exposure, competitive positioning, and long-term growth prospects. These expectations push companies to incorporate detailed narrative explanations within annual reports, integrated reports, sustainability disclosures, and investor briefings. This narrative reporting must articulate brand strength, reputation metrics, customer loyalty indicators, and intangible performance drivers. Yet companies must provide such disclosures while remaining compliant with IFRS constraints and protecting sensitive competitive information.

Achieving this balance presents significant challenges. Companies must determine how much brand-related information to disclose without compromising proprietary strategies. They must also ensure consistency in narrative reporting, valuation assumptions, and financial statement notes to maintain credibility. This interplay between regulatory transparency and strategic confidentiality forms the complex reporting landscape that characterizes brand disclosures within Singapore’s corporate environment.

Valuation, Impairment, and Disclosure Difficulties

Estimating Useful Life and Impairment Triggers

Determining the useful life of a brand is one of the most subjective and conceptually challenging tasks within intangible asset accounting. Brands are not consumed physically; they evolve based on cultural trends, consumer perception, industry competition, and strategic execution. Some brands endure for generations, maintaining relevance and loyalty through continual evolution, while others face rapid decline due to reputational events, technological disruption, or changing consumer behavior.

IAS 36 requires companies to classify brands as finite-lived or indefinite-lived assets. Finite-lived brands must be amortized over their useful life, while indefinite-lived brands require annual impairment testing. Determining an indefinite useful life requires assessing whether there is foreseeable limit to the brand’s economic benefits. This requires evaluating brand recognition, market share stability, competitive positioning, loyalty metrics, intellectual property protections, and historical performance. These assessments require significant judgment and must be revisited annually.

Impairment triggers introduce additional challenges. Brands are vulnerable to reputational crises, supply chain disruptions, economic downturns, regulatory changes, or shifts in consumer sentiment. A single negative event—such as a recall, scandal, or social media backlash—may necessitate impairment testing. Companies must monitor both internal and external indicators, interpret market signals, and determine whether impairment is necessary.

Impairment models rely on subjective assumptions, including long-term growth rates, discount rates, risk premiums, and brand-specific cash flow forecasts. These assumptions must be documented, justified, and stress-tested. Because small changes in assumptions can dramatically alter valuation outcomes, impairment testing remains one of the most sensitive and challenging areas of financial reporting.

Disclosure Limitations and Stakeholder Interpretation

While IFRS requires disclosures of valuation methodologies, key assumptions, and impairment judgments, these disclosures are often insufficient to convey the true nature of brand performance. Quantitative disclosures do not fully communicate the drivers behind brand strength, such as reputation resilience, customer loyalty, innovation, cultural relevance, digital engagement, and sustainability alignment. Investors increasingly demand deeper insight into these qualitative factors.

Companies must therefore rely heavily on narrative disclosures to convey brand strategy and performance. Narrative disclosures allow companies to describe brand positioning, competitive differentiation, market opportunities, reputational risks, strategic goals, and intangible value drivers. However, narrative reporting is subjective and varies widely across companies, creating challenges in comparability and reliability.

Companies must also avoid providing excessive detail that may expose competitive strategies or create legal risk. The tension between transparency and confidentiality becomes a central challenge in brand reporting. Companies must navigate these complexities carefully to maintain credibility with investors while safeguarding strategic interests.

Conclusion to Accounting and Reporting Challenges in Brand Valuation

Brand valuation stands as one of the most challenging areas of modern corporate reporting due to the inherent subjectivity of intangible assets, the restrictive recognition rules of IFRS, and the rapidly growing stakeholder demand for transparency and insight. The visibility gap created by IAS 38, the judgment-heavy requirements of IAS 36, and the complex narrative expectations of investors create a landscape that demands exceptional analytical rigor and strategic communication.

In Singapore, these challenges are amplified by high governance standards, sophisticated investor expectations, and a business environment driven by innovation and intangible value creation. Companies must address significant brand reporting challenges IFRS and navigate brand accounting issues Singapore by combining strong compliance practices, advanced valuation methodologies, and compelling narrative reporting. The future of brand accounting will likely require deeper integration of quantitative and qualitative reporting, ensuring that financial statements and supplementary disclosures together capture the full spectrum of brand-driven value in the modern economy.